The Emerging Empirical Science of Wisdom

'Understanding Wisdom' Series

We are continuing our exploration of the topic of wisdom after my previous articles, the three-part post on the Polyhedron Model of Wisdom, and the 6P Unified framework. The model we will examine now is detailed in the 2019 research paper The Emerging Empirical Science of Wisdom: Definition, Measurement, Neurobiology, Longevity, and Interventions by Jeste, Dilip V. MD; Lee, Ellen E. MD. Their paper provides an extensive overview of the empirical research on wisdom. It delves into the definition, measurement, neurobiological basis, and the evolutionary significance of wisdom, while also discussing how wisdom changes with aging and potential interventions to enhance it. Here is a summary of its key points.

Introduction and Historical Context

Wisdom has been a topic of deep contemplation and reverence across cultures and centuries, often discussed within the realms of religion and philosophy. From the ancient scriptures of the Bhagavad Gita to the philosophical musings of Socrates, wisdom has been celebrated as a pinnacle of human development. However, as Jeste and Lee point out, “Empirical research on wisdom began to take shape in the 1970s, paralleling the scientific inquiries into other psychological constructs such as consciousness, stress, and well-being.” Despite this, wisdom remains a concept that many find challenging to define, operationalize, and measure with precision.

The article by Jeste and Lee serves as a comprehensive overview of the burgeoning field of empirical wisdom research. The authors aim to bridge the gap between the traditional, often abstract discussions of wisdom and the emerging scientific approaches that seek to understand wisdom as a measurable and biologically grounded construct. They emphasize that wisdom is not merely an esoteric ideal but a complex human trait with significant implications for both individual and societal well-being.

Defining Wisdom: A Complex Trait

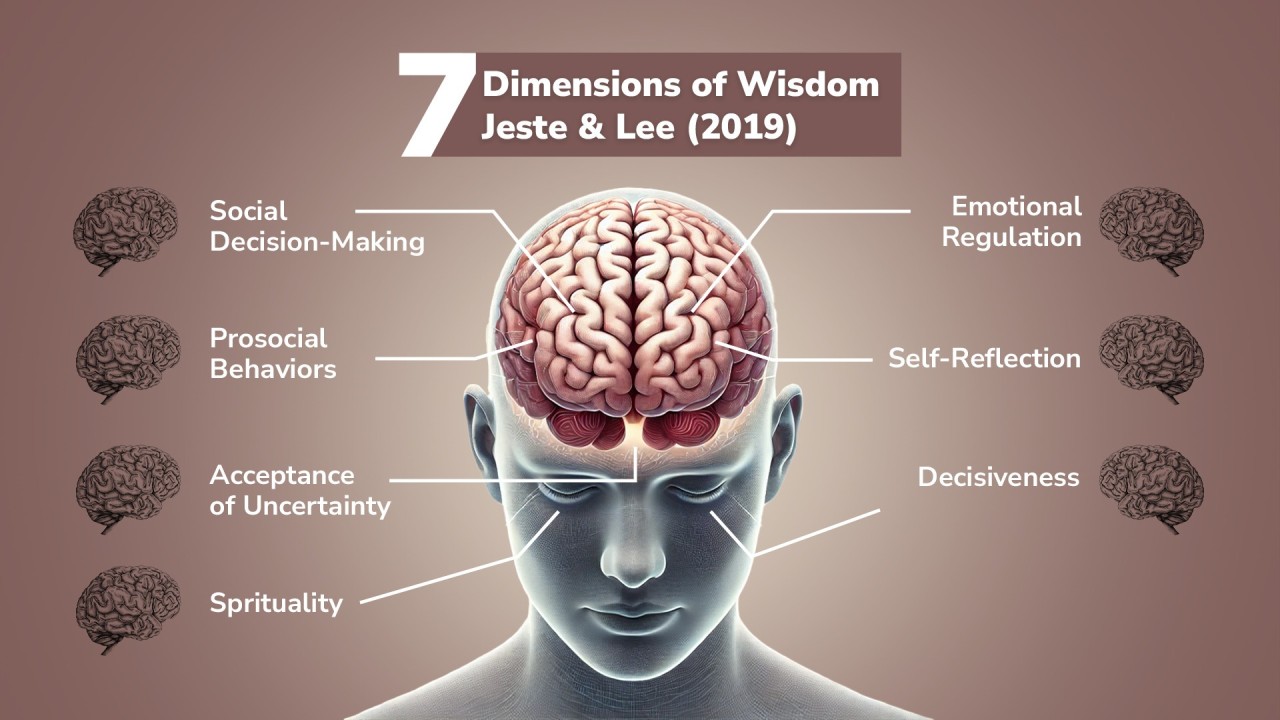

The definition of wisdom has evolved over time, reflecting the multidimensional nature of the concept. Wisdom, as defined by Jeste and Lee, encompasses several key components: social decision-making, emotional regulation, prosocial behaviors such as empathy and compassion, self-reflection, acceptance of uncertainty, decisiveness, and spirituality. These components, they argue, are not merely philosophical or moral ideals but are grounded in specific neurobiological processes. “Wisdom is a multidimensional trait that is useful both to the individual and to society,” the authors note, emphasizing that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

The complexity of wisdom is further highlighted by the diverse methods used to define and measure it. For instance, historical definitions of wisdom often emphasized moral and ethical aspects, while modern definitions incorporate psychological and neurobiological perspectives. The Oxford English Dictionary, for example, defines wisdom as “the capacity of judging rightly in matters relating to life and conduct,” while empirical researchers have sought to operationalize wisdom by breaking it down into measurable components.

Jeste and Lee review several approaches to defining wisdom. They highlight a literature review by Meeks and Jeste, which identified six common components of wisdom: general knowledge of life and social decision-making, emotional regulation, prosocial behaviors like compassion and empathy, insight or self-reflection, acceptance of different value systems, and decisiveness. The authors also mention the influence of spirituality and openness to new experiences, which have been proposed in some studies as additional components of wisdom.

Measuring Wisdom: From Theory to Practice

The empirical study of wisdom requires robust methods for measuring this complex construct. Jeste and Lee discuss various scales and methodologies that have been developed to assess wisdom, each with its strengths and limitations. “A requisite for good empirical studies of any construct is its optimal measurement,” the authors assert, highlighting the importance of reliable and valid measures in advancing the science of wisdom.

One of the earliest and most influential approaches to measuring wisdom is the Berlin Wisdom Paradigm, developed by Baltes and colleagues. This approach views wisdom as a set of measurable skills, with respondents being asked to solve complex, hypothetical life dilemmas. Their responses are then rated according to five elements of wisdom: rich factual knowledge, deep procedural knowledge, lifespan contextualism, relativism, and acceptance of uncertainty. However, as Jeste and Lee point out, this paradigm has limitations, including its reliance on the subjective interpretations of raters and its lack of emphasis on emotional and prosocial components of wisdom.

In contrast, self-report scales have become increasingly popular in wisdom research due to their ease of use and ability to capture subjective experiences. Two widely used scales are the Three-Dimensional Wisdom Scale (3D-WS) and the Self-Assessed Wisdom Scale (SAWS). The 3D-WS assesses cognitive, reflective, and affective dimensions of wisdom, while the SAWS focuses on critical life experiences, reminiscence, openness to experiences, emotional regulation, and humor. These scales have been validated in various populations and have shown good psychometric properties, making them valuable tools for both research and clinical practice.

The San Diego Wisdom Scale (SD-WISE), developed by Thomas and colleagues, represents a more recent advancement in wisdom measurement. This scale is the first to build upon a putative neurobiological model of wisdom, assessing the six commonly identified components: social decision-making, emotional regulation, prosocial behaviors, self-reflection, acceptance of uncertainty, and decisiveness. In an initial validation study, the SD-WISE was found to be reliable and demonstrated convergent and discriminant validity. As Jeste and Lee suggest, “The SD-WISE may be useful in both clinical practice and research settings,” offering a more comprehensive and biologically informed measure of wisdom.

Despite the progress made in measuring wisdom, challenges remain. One common criticism of self-report measures is the potential for social desirability bias, where participants may rate themselves more positively to present a favorable self-image. However, Jeste and Lee argue that self-reports can still be valid, especially when measuring subjective constructs like well-being. They also highlight the importance of developing multimodal assessments that combine self-reports with behavioral observations and neurobiological data to obtain a more holistic understanding of wisdom.

The Neurobiology of Wisdom

The exploration of the neurobiological underpinnings of wisdom represents one of the most exciting frontiers in wisdom research. Jeste and Lee propose that wisdom is not just a psychological or moral trait but has a concrete basis in the brain’s structure and function. They review the literature on neuroimaging, genetic, neurochemical, and neuropathological associations with wisdom, offering a tentative model of the neurocircuitry underlying this complex trait. Note that I chose not to elaborate on this aspect of their paper, to keep it brief. Those who are interested to know more can read about it in the original article.

“Wisdom likely involves several different neurocircuits, neural contexts, and brain regions,” the authors explain. The prefrontal cortex (PFC), particularly the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), plays a central role in social decision-making, emotional regulation, and acceptance of uncertainty—key components of wisdom. The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) is implicated in prosocial behaviors, moral reasoning, and self-reflection, while the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) is important for decision-making regarding delayed rewards and impulse control.

The interaction between these frontal brain regions and the limbic system, including the amygdala and ventral striatum, is crucial for balancing emotional responses with rational decision-making. Jeste and Lee describe how the lateral PFC inhibits activity in the amygdala, helping individuals regulate their emotions and make decisions that align with their long-term goals rather than succumbing to immediate emotional impulses.

One of the most famous cases highlighting the neurobiological basis of wisdom (or the lack thereof) is that of Phineas Gage, a 19th-century construction foreman who survived a traumatic brain injury that severely damaged his left frontal lobe. Gage’s personality changed dramatically after the injury, shifting from a disciplined and well-liked individual to someone who was impulsive, profane, and socially inappropriate. This case and others like it demonstrate the critical role of the prefrontal cortex in maintaining behaviors that are characteristic of wisdom, such as self-regulation and social appropriateness.

Further supporting the neurobiological basis of wisdom, Jeste and Lee discuss studies on frontotemporal dementia (FTD), a condition that primarily affects the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. FTD is often characterized by changes in personality and behavior, including impulsivity, poor social awareness, and a lack of empathy—traits that are antithetical to wisdom. These findings suggest that the integrity of the prefrontal cortex and its connections with other brain regions is essential for the expression of wisdom.

领英推荐

The Evolutionary Significance of Wisdom and Aging

Wisdom is not only a psychological and neurobiological phenomenon but also an evolutionary one. Jeste and Lee propose that wisdom has an important role in the survival and fitness of the human species, particularly through the contributions of older adults. They introduce the “Grandma Hypothesis,” which posits that post-reproductive women contribute to the survival and well-being of their grandchildren, thereby enhancing the reproductive success of their offspring.

Despite the physical decline associated with aging, older adults often report greater well-being and happiness compared to younger individuals. This paradox of aging, where subjective well-being increases despite declining physical health, may be partly explained by increases in wisdom. As Jeste and Lee note, “Several studies have suggested that wisdom (or its components) increase with age,” contributing to better emotional regulation, prosocial behaviors, and overall quality of life in older adults.

The authors cite evidence from cross-sectional studies showing that older adults tend to perform better on tasks related to social reasoning, emotional regulation, and empathy compared to younger adults. For example, research on Theory of Mind tasks, which assess the ability to understand and predict others’ thoughts and feelings, has shown that older adults often outperform younger ones. Similarly, older individuals are more likely to consider long-term consequences in their decision-making and to draw upon their life experiences to navigate complex social situations.

The evolutionary benefits of wisdom are not limited to humans. Jeste and Lee reference studies on other species, such as orca whales and Asian elephants, where post-reproductive females play a crucial role in the survival and reproductive success of their social groups. In humans, the presence of grandparents has been associated with better outcomes for grandchildren, including fewer emotional problems, better social adjustment, and greater reproductive success in adulthood.

The authors also discuss the genetic basis for the evolutionary advantages of wisdom. Certain genetic variants, such as those related to the CD33 gene, which suppresses the accumulation of amyloid-beta peptide in the brain, may protect against neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. These “grandparent genes” may have evolved to enhance the contributions of older adults to the survival of their kin, further supporting the idea that wisdom has a critical role in human evolution.

Wisdom-Related Neuroplasticity and Interventions

The concept of neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to reorganize and adapt in response to experiences and environmental stimuli, is central to understanding how wisdom can develop and change over the lifespan. Jeste and Lee suggest that while aging is generally associated with cognitive decline, the brain remains capable of growth and adaptation, particularly in areas related to wisdom.

Physical activity, cognitive stimulation, and social engagement have been shown to promote neuroplasticity in older adults, leading to increased synaptic connections, cerebrovascular growth, and even neurogenesis in certain brain regions. These findings suggest that engaging in activities that challenge the mind and body can help maintain or even enhance wisdom-related cognitive functions in later life.

Moreover, the authors propose that wisdom can be enhanced through targeted interventions. They review studies on various interventions aimed at increasing specific components of wisdom, such as empathy, emotional regulation, and spirituality. For example, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of life review therapy in older veterans with PTSD found that the therapy was associated with increased wisdom, as measured by the Self-Assessed Wisdom Scale (SAWS). Another study on empathy training in young adults showed that the intervention led to increased activation in brain regions associated with empathy and compassion, suggesting that such interventions can have a measurable impact on the neurobiology of wisdom.

Jeste and Lee emphasize the need for more rigorous research on wisdom-enhancing interventions, particularly those that target multiple components of wisdom simultaneously. They argue that interventions combining behavioral, cognitive, and emotional training could have a greater overall impact on well-being than those focusing on a single aspect of wisdom. The authors also call for the development of new technologies, such as biofeedback and virtual reality, to facilitate and enhance these interventions.

Implications and Recommendations for Future Research

In their conclusion, Jeste and Lee highlight the broader implications of their research for both individuals and society. They suggest that the development of wisdom, particularly in older adults, could help address some of the major challenges associated with aging, such as declining mental health and well-being. By promoting wisdom through targeted interventions and educational programs, society could enhance the quality of life for individuals across the lifespan.

The authors offer several recommendations for future research in the field of wisdom. They call for more studies on the relationship between wisdom and physical health, including the identification of biomarkers that could serve as indicators of wisdom-related neuroplasticity. They also suggest that research should focus on understanding the role of wisdom in neuropsychiatric disorders, such as frontotemporal dementia, where deficits in wisdom-related behaviors are particularly pronounced.

Another area of interest is the potential for intergenerational programs to foster wisdom in both younger and older adults. Jeste and Lee reference the Baltimore Experience Corps, an intergenerational program where older adults serve as mentors and tutors for children in elementary schools. This program has been shown to improve outcomes for both the children and the older adults involved, suggesting that such initiatives could be a powerful tool for enhancing wisdom and well-being across generations.

Finally, the authors argue that wisdom should be integrated into educational curricula, from elementary schools to professional training programs. They note that while traditional education has focused on intelligence and academic skills, these do not necessarily translate into greater well-being or life satisfaction. By incorporating wisdom-related skills, such as emotional regulation and prosocial behaviors, into education, society could better prepare individuals to navigate the complexities of modern life.

Conclusion

Jeste and Lee’s article on the emerging empirical science of wisdom highlights the multidimensional nature of this complex trait. Wisdom, they argue, is not just a philosophical ideal but a measurable and biologically grounded construct with significant implications for individual and societal well-being.

The authors emphasize that wisdom is a dynamic trait that can be developed and enhanced throughout life, particularly through targeted interventions and supportive environments. They call for continued research to further understand the neurobiological underpinnings of wisdom and to develop effective strategies for promoting wisdom across the lifespan.

In conclusion, wisdom is a vital component of human thriving, with the potential to enhance mental health, well-being, and social harmony. As Jeste and Lee summarize, “There is a need to expand empirical research on wisdom, given its immense but largely untapped potential for enhancing mental health of individuals and promoting well-being of society at large.”

Leadership & Life Coach (ICF/PCC) | Mentor | Business Consultant | Practitioner and student of Meditation,Spiritual Study,and Vedic Chanting

1 个月Thank you for this comprehensive summary Surya Tahora . The authors seem to have done a 360 on wisdom, touching upon numerous perspectives. I also appreciate their findings which relate aging and wisdom, something I have experienced first hand.